2015öNōx ŖwÅpīŚ¼ÄxēćÄæŗÓ ŖCŖOé╠æÕŖwōÖéŲé╠ŗżō»ŖwÅpŖłō«Äxēć

(āvāŹāWāFāNāgNo.1-4 Ŗ┬ŗ½éŲŖJöŁé╠āWāIāCāōātāHā}āeāBāNāX)

Ģ±ŹÉÅæ

āvāŹāWāFāNāgæŃĢ\ü@īĄü@¢įŚč

Ŗ┬ŗ½ÅŅĢ±ŖwĢöŗ│Ä÷ü@īōÉŁŹ¶üEāüāfāBāAīżŗåē╚

Toward A Cultural City of Kesennuma From 3.11

in Tohoku Japan

Charrette Design Workshop on the Reconstruction of Matsuiwa-Omose

Area

Wanglin

Yan

Faculty of Environment and Information Studies

Keio University

1.

Introduction

Kesennuma

City is a city located at the central of Sanriku

costal region and the northeast corner of Miyagi Prefecture with 334 km2

of land and 65,430 population (2015/09). The ria landscape forms the most part of the city with

serrated coastal lines, drowned valleys, and deep bays beneficiary for

aquaculture, especially oysters and scallops. Fishery industry provides major

job chances for the city itself and the region. In the Great East Japan

Earthquake of March 11, 2011, an earthquake registering nearly 6 on the

Japanese seismic scale (comparable with Richter scale from 1 to 6) was measured

in the city center area, and nearly 5 in Motoyoshi

area, the south part of the city. The tsunami subsequently swept the bay area,

landed big ships, flooded the downtown and main business districts. Leaked oil from the broken tanks induced disastrous fires burnt Shishiori, another population dense area. The city as a

whole counted 1359 casualties, including 220 missing persons and 108

related-deaths, damaged 15,815 houses and 9500 families.

The big fire and the landed ship in in Shishiori

demonstrated the severity of the disaster. Half year later after the event, the

city authorized the Reconstruction plan in October of 2013. The Master plan set

the goal of reconstruction in ten years while the first 5 years is intensive

reconstruction period for a safe, workable, livable, sustainable, joyful, slow

and smart city in 10 years. The master plan was embodied by seven pillars:

reconstruction of the infrastructure, rehabilitation of disaster management,

renewal of industry, restoration of nature-human dynamics, enhancement of

healthcare and wellness, improvement of learning and education, and promotion

of community activities, with 31 sub-projects in total. For the realization of

the plan, it calls for cooperation of all stakeholders including citizens,

industrials, government and NPOs etc.

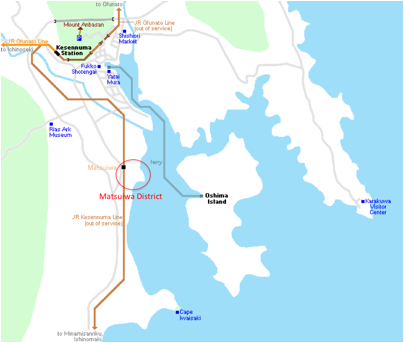

Fig.1 Layout of Kesennuma City and the

targeted area

Five years has passed, and the city has been gradually recovering. The rubles

were cleaned in first three years, and the road infrastructures are in

reconstruction. The low land in city center were readjusted and elevated for

industrial and commercial activities while the reconstruction of other

inundated areas are largely delayed. The inundated low lands under the tsunami

line are regulated for residence. Citizens who lived there have three choices:

1) move to higher land if land is available personally and affordable for a

detached houses by themselves independently; 2) relocate to higher land

collectively if land is available by group and affordable for a detached house

independently; 3) relocate to a unit of city-owned condominiums in cheap rent.

While the projects of relocation are steadily progressed, the reconstruction of

inundated areas is largely delayed, particularly the land out of city center. This

is partly because of capacity of human and financial resources. The main reason

of delay comes from the uncertainty of the land use policy. What to rebuild in

the remote and shrinking city? The population of the city has decreased by 9.4%

in recent five years after the disaster.

The District of Matsuiwa, the target area of this workshop, is one of such an

areas. The district is located 5km south of the city center. The houses along

the coast and the river were swept away by the tsunami. The shrine of Ozaki at

the cape is located on a top of a hill where more than 30 evacuees survived. Enunkan, a historical house of Ayukai

family since Edo era and also the home of Mr. Naofumi

Ochiai, a famous Japanese literature in Meiji era,

just sits at the north above the tsunami line, in front of the bay with a

beautiful Japanese garden and a nice view of the harbor.

|

Fig.2. The historical house of Enunkan |

Fig.3 The Shrine of Ozaki that saved 30 evacuees from Tsunami |

|

|

Fig.5 After the tsunami |

Even with such a nice location and rich cultural-natural resources the

municipality owns no idea about the reconstruction of the area. Previous residents,

landowners and citizens are interested in rebuilding the district as a compound

zone for recreation, learning, and communication. They have started to talk and

have developed some ideas. They do not know how to represent the ideas

professionally in harmony with the landscape and culture, and how the ideas

could be implemented and contribute to the future of the city. This might be

the good chance to reconstruct the area with participation of public through

bottom up process. In context, a design charrette was organised to design a reconstruction

plan with participation of experts and local residents during Sep 7 to 11, 2015.

The aims of this workshop are:

1)

Understanding the

demands, wishes and interests of the people (residents and outsiders)

2)

Work together with

the people in co-creation (residents and outsiders)

3)

Develop a plan for

a future vision of the region

4)

Design the pathways

and spatial alignments of Matsuiwa District

5)

Making

recommendations for implementation of the plan and the design

2. Processes of the

workshop

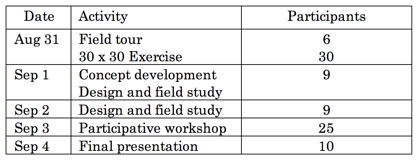

The charrette workshop was held over four consecutive days, from August

31 to September 3, 2015 at Kesennuma Kingüfs Village (Matsuzaki-omose 17-1). It is organized by Keio University

incorporated with Swinburne University of Technology, VHL University of Applied

Sciences, and EME Design under the support of Association of UNESCO Kesennuma, and Association of Livable City Kesennuma, and Australia Japan Foundation.

The schedule of the workshop is summarized in Table 1. Residents and

local activists were invited to participate in a üg30 x 30 Exerciseüh in the evening of August 31, and a participative

design workshop in the evening of September 3. Geographic data and documents

about the area were prepared beforehand for experts. Experts and participants

stayed at the facility, which is located in the design area, easy to walk

around and talk with local people.

Table 1 Process of the charrette workshop

The 30 x 30 Exercise is essentially a

brainstorming session with local residents and experts reflecting together on

how the region was 30 years in the past and how it could become 30 years in the

future (Roggema 2013). A total of 30 participants

broke into four groups and gathered around the tables bearing signs indicating

four themes: Population, Economics, Culture, and Environment. They discussed

the situation 30 years ago, wrote key words on ügsticky notes,üh and placed them

on aerial photographs. Several minutes of brainstorming was allowed for each

theme, with the post-it notes left on the maps. The participants subsequently

moved to the next table and added ideas during a seven-minute brainstorm about

their second topic. Eventually, all participants conducted a brainstorm on each

of the four themes. Finally, the team leaders at each table presented a

three-minute summary at each table of the results up to that point. Through

this process, each group reconfirmed things such as what existed in the area in

the past, what was lost, and what should be kept for the future. The output of this

process is summarized in Table 2. It is full of messages about the natural and

cultural resources.

The

second round of 30*30 Exercise is used for participants to picture the future

of the area in 2045. The participants were separated into four groups and each

group was assigned at a table with aero photo as base map. Each group is

required to draw their ideas on the base map for the reconstruction by using

the resources discussed in previous session. At the end each group had 5min to

present their proposals.

Fig. 6 30*30 Exercise and design proposals from participants

3. Design by expert team

The 30*30 exercise was the first time for residents from different

districts in this area to talk about the past and future together. It collected

rich information about the natural and cultural resources of the study area.

3.1 Understandings of the area

The design area is located at the mouth of Omose

River, a second-order river maintained by Miyagi Prefecture. The two sides of

the river belongs to different administrative

district, Matsuiwa District on left side and Omose District on right side. Each district was composed of

many communities with individual history. Depending on the loss and damage

during the tsunami, the residents demonstrates different responses. The Ozaki

area in Omose District where all of the houses were

swept and most the citizens evacuated to the temporary houses in a same

evacuation site moved speedily. Their lands was fully bought up by the

municipality, a sport park is going to be build. Situation in Matsuiwa District was quite complicated. The tsunami line

encroached residence and farmlands inland and separated the communities in low

land and upland. Afraid of the damage of tsunami, inundated families has given

up to live there and moved their houses to higher lands. There is a big

difference of concerns toward the reconstruction of the low land. Except

tsunami disasters, the area is prone to flood. A large part of the area was

under the sea level. The residence so far was protected well-developed drainage

systems and a pump station. Therefore, the reconstruction should not only think

about the protection from the sea but also the risks from mountains. The design

area at the river mouth should be considered by river basin, crossing the

administrative zones.

The development of the area origin to the Enunkan,

the old house of Ayukai

family and Japanese Linguist Naofumi Ochiai. The ancestor of the family was a vassal of Date Domain and moved from Yamagawa Prefecture 500 years ago. The old house Enhunkan, the family shrine Hachiban

Shrine standing at the terrace of hills, and Ozaki Shrine at the cape of Ozaki

area compose a gold triangle of the landscape of the area. People who have lived

in the area for hundreds of years have been fishing in the sea, cultivate the

paddy fields, excavated gold in mountains, and lumbered timbers in forest, and

developed a lot of folk tales and traditional activities. The reconstruction of

the design area should be placed in the historical and ecological context of

the entire from coast to the upper streams of rivers and mountains.

As the gateway to the city center from south coastal part of the

prefecture, multiple reconstruction projects at regional scale pass through the

area. Sanriku Highway from Sendai City to Iwate

Prefecture cut through the west of the area with an interchange. The national

route 26 runs through the coastal line from south to north under the Hachiban Shrine. One side of river dire is in

reconstruction from the fishery harbor to upper stream of Omose

River till the national route. All of the civil engineering projects are

rebuilt on the elevated basement higher than 10.0m, the height of the last

tsunami. The limited space of the area is going to be gridded by giant concrete

bodies with sunken between the grid. Each of the projects is planned and

constructed by different administrative agencies with collaboration each other.

The projects are planned and designed only to meet the specification of

engineering, lack of consideration of the harmonization with nature and

culture. Local communities and residents, the people who know the situation,

are outcasted from the process.

3.2 Concept of the design

The 30*30 Exercise and the field tours, the

design team understood that the area has rich natural and cultural resources;

it was a prone to disasters of tsunami and flood; reconstruction projects are

ongoing in part of the area with harmonization and collaboration. What the most

important is that we should change our

mindsets from protection from disaster to adapt to disasters. The design team understood that

reconstruction must, 1) remember the

past for the future generations; 2) reconnect

the sea with mountains; 3) reform the

rigid protection-based reconstruction to resilient reconstruction by adaptive

planning. The first one, remember, is

self-evident in a post-disaster reconstruction. Many cities have reserved

damaged buildings and ruins in memorial parks as materials for disaster

education. However, the implementation of the idea and utilization of the

facilities are context-dependent. We believe that the memorial should not be

the decoration or an exhibition of the history. It must be the life of the

people. The contents, the scale, and the location should be considered in

social ecological systems of the area. This comes to the second idea reconnect. The design area is a flood

plain at the mouth of Omose river.

The development of the flood plain backed to the gold mining the upper stream

of the river, which shapes the landscape largely, and reserved a lot of stories

in the gold rush time. The most famous one is the tale of Oiran,

a beautiful girl who made up by the flourish water of Omose

River as perfume to serve served gold miners. Many other local stories are

inherited in this region. Moreover, a collective relocation project is ongoing

in 2km upper stream. Most of the residents of the collective housing district

are those who lived in the design area. Therefore, the sustainability of the

river mouth must be considered with the river basin together. The realization

of this idea requires the third point: reform.

The disaster is a window for the area to rebuild transformatively.

Reconstruction projects should be placed in the social-ecological system of the

area in harmonized with nature and culture. This requires reform of

reconstruction concepts, reform of administration and reform of peopleüfs

mindsets. Reconstruction is not simply resuming the situation before the disaster.

It must be the construction for the development of next generations. It will be

a starting point of a new story, which reflected the lessons we learnt, and the

prospect we look for. Rather than the area itself, we should stand at the scale

of the whole city or above to think about what the area should be like, who

should be involved, what the functions should be included, and how it could be

realized. Landscape design is a platform to collect fragmented information,

place them on the table, realign them spatially, and communicate with people

for realization.

3.3 Design

Considering the geographic location, we set the goal of the

reconstruction is to rebuild the area as a complex of creative culture with a

combination of diverse components harmonized with En-unkan,

Hachiban Shrine, Ozaki Shrine and the bridge of Sanriku Highway with Oshima in

background. These components are,

1)

Old stories and

new stories related to remember,

(1) Cherry line planted along tsunami line

(2) A 93.3*93.3m2 memorial park embedded with

the streets before the disaster of the area in 1 to 10 scale

(3) Use of debris material to shape the old street

patterns and house locations/foundations

(4) Think water as a friend to live with and give it more

space to absorb risks by traducing water into the ground 0 area.

(5) Receive and downsize floods by dissipative structure

of coasts

2)

Reactivating

natural and cultural resources by reconnect,

(1) visually

anchor Enunkan - Hachiban

Shrine - Ozaki Shrine, and the new monument as a diamond of the landscape

(2) Connect the hinterland

with the seaside by extending the hills to the sea

and allow water inlands

(3) Mitigate flooding

from mountains by widening the streams

(4) Create history sites

(cat stone, mirror stone), along the route inland

(5) Ask relocated people

to garden their former house in excavation zone

(6) Bicycle path,

connecting hills, historic story-points with new monument, shrines and sports park

3)

Embrace regional

infrastructure for implementation by reform,

(1) Use the levee in construction along Omose River as access promenade to the central square

(2) Build bus stop and parking at the intersection of the

national route and the levee as entrance

(3) Shape up the beach with sports park including football,

tennis, baseball, swimming with amphi-theatre for

spectators

(4) Allow relocated people to garden their former house

(vegetables, flowers)

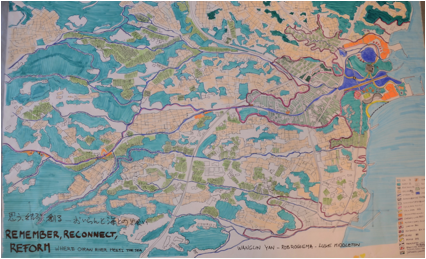

Fig.6 The landscape design: Remember,

Reconnect, Reform (Central Area)

Fig.7 The Landscape Design (The entire

Area)

3.4 Communication with participants

The residentsüf design workshop was held at

the end of the design charrette process. The findings of the design team were

presented in a presentation to the group, then a plasticine

model was created to show the impacts of the design in three dimensions, and

finally a participatory design workshop was held with citizens.

1) Presentation

preparation

In the preparation

process for the presentation the overall design process was reviewed, which

helped to clarify the message of the design proposal. Through the 30 x 30

Exercise, the flow of the process became clear. Participants had the

opportunity to ügrememberüh the

experience and history of area. The design for reconstruction from the disaster

presents the opportunity for the regional natural and cultural intrinsic to be ügreconnectedüh. After remember and reconnect,

the ügReformüh can occur. By ügreformüh two aspects are meant. First,

the people reform the way of living for sustainability, and second, people

could physically reform to their land by collaboration. This conceptual

approach was presented to the residents, and then, in order to incorporate the

residentsüf perspectives, three-dimensional models were created using plasticine to visualize the outcomes.

2) Visualizing

the design concepts using three-dimensional models

Plasticine is useful as a tool to express the ideas of

participants (Roggema, Vos,

& Martin, 2014). Using plasticine,

which is available everywhere, participants could visualize the connections

between the spatial components of identity in the region, and they could design

their desired configurations of added and existing landscape elements. The

landscape elements that were designed on paper suddenly become

three-dimensional. Anyone can easily join, because of the common childhood

experience of playing with clay, the material is inexpensive, and it

facilitates dynamic communication.

3) Design

workshop

A participatory design

workshop was held at the Ota Community Center. The participants consisted of

the same groups as in the 30 x 30 Exercise. Before the workshop, the design

proposals, the landscape plan, and a demonstration of the plan by plasticine models were presented and exhibited at the

venue. At the start of the workshop, the design team gave a presentation on the

theme of ügRemember, Reconnect, Reform.üh After questions and answers, participants were

divided in four groups and asked to use the plasticine

to express how they envision a plan for reconstruction, on top of aerial photos

(Fig.8). Because of the fact that the participants were informed and saw the

expertsüf designs and the three-dimensional models in advance, the workshop went

smoothly. Students, workers, and seniors, all generations from various

occupations, worked together as unified teams to think about the regionüfs

future, expressing their ideas by use of plasticine

and placing the items physically on the aerial photograph. It was a dynamic

exercise, with participants adjusting each otherüfs creations and their spatial

relationships. Some participants asserted their ideas strongly and sought

agreement from everyone, while others yielded more and made an effort to

consolidate the discussions. All of the teams were keen to develop their plans.

This session was an important opportunity for communication and to understand

what others were thinking.

At the end, each team

leader made a presentation, explaining the spatial alignment and proposal

developed by the group. For many students from local high school this was the

first time to participate in such a design game and to speak in front of a

group of people. They proudly introduced their teamüfs work and they felt happy

with such a positive experience.

Fig.7 Plasticine Model made by participants

Fig.8 Participants are working together

Fig.8 Close-up of the plasticine model

4. Discussion and Conclusions

It was first time to hold the participate

workshop for the reconstruction in Matsuiwa Area

which bring people together from different district. Last plan has been made

with the help of Tohoku Gakuin University and

delivered to the municipality four years ago. At that time, 95% of the

residents have chosen to move to higher lands while only 2.5% of residents

selected to return. Without request from residents, the municipality cannot do

anything. On the other hand, residents thought that they have sent their

requests and the city government should have move on. Unfortunately, nothing

has happened during the period.

The design proposal was built on the

analysis of the situation at the regional scale and river basin scale.

Participants of the workshop were delightful to see an alternative from the

conventional one, a simple collection of infrastructure projects and the

requests of residents. By change of ideas, the city could be safer, livable and

smarter.

It is surprised that the participants showed

strong concerns on cultural and recreational facilities while the safety was

not touched very much in the preliminary design and final design workshop. This

may reflect that residents would take the safety granted even in a city not

long after a disaster. On the other hand government has paid more attention on

safety issue by swift reconstruction of levee and the elevation of roads. This

difference might be the reason of the gaps between residents and municipality. Participative

design workshop is effective to visualize all of the projects and information

in one map.

Acknowledgements

This project is granted by Academic Exchange Grants of the Graduate

School of Media and Governance, Keio University in fiscal year 2015. The charrette design workshop was supported by the Associate of Sumiyosa Kesennuma City.

We are grateful for Kingüfs Garden Miyagi Ltd to provide us the accommodation of

Kingüfs Village during the workshop.

Roggema,

R., Vos, L., & Martin, J. (2014). Resourcing local communities for climate

adaptive designs in Victoria, Australia. Chinese Journal of Population

Resources and Environment, 12(3), 210–226.

doi:10.1080/10042857.2014.934951