Mori Grant Final Report

|

{0><}100{>Name of the Research Project<0} |

Nuclear Energy vs. Human Security - A case

study of nuclear power plant |

|

{0><}100{>Name of the Research Project Leader<0} |

Tarek Katramiz |

|

Affiliation |

Graduate School of Media and Governance <0} |

|

Type

of Program (Circle one) |

Master’s Program |

|

Student

Year |

Second Year |

|

{0><}100{>Telephone Number<0} |

090-80442275 |

|

Email

Address |

tarek.katramiz@gmail.com |

Overview:

Japan is considered as the “Most Earthquake-Prone country in the world owing mainly to its geographical location. There have always been many concerns about the ability of Japan nuclear plants to withstand the seismic activity that Japan is characterized for. Many minor incidents occurred irregularly since the nuclear energy had been introduced in 1973. One minor incident was when the Kashiwazaki- Kariwa nuclear plant was completely shut down for 21 months following an earthquake in 2007. However, in terms of consequences of radiation release, worker exposure, and core damage the Fukushima I nuclear accidents in 2011 were the worst experienced by the industry in addition to ranking among the worst civilian nuclear accidents. Now there are more concerns than before about the vulnerability of Japanese nuclear industry as it imposes a major threat on the livelihood of the host communities who live nearby the plants. Opposition to nuclear power has long existed in Japan and a 2005 International Atomic Energy Agency survey showed that "only one in five people in Japan considered nuclear power safe enough to justify new plant construction".

When it comes to earthquake possibility, the Tokai region is a vulnerable area for nuclear plants as the major Tokai is said to be overdue. Hamaoka nuclear plant is built in Shizuoka prefecture (Tokai region), it is built directly over the subduction zone near the junction of two tectonic plates. Dr. Kiyoo Mogi, a prominent Japanese seismologist, pointed out the possibility of a major earthquake in 1969 just 7 months before it was permitted to construct the Hamaoka plant[1]. Also, Prof. Katsuhiko Ishibashi, a former member of a government panel on nuclear safety, claimed in 2004 that Hamaoka is considered to be the most dangerous nuclear power plant in Japan, with the potential to create 原発震災 (domino-effect nuclear power plant earthquake disaster)[2]. Following the protestor calling for the Hamaoka power plant to be shut down, On 6 May, 2011, prime minister Naoto Kan requested the plant to be shut down in light of the fact that an earthquake of magnitude 8.0 or higher is estimated 87%likely to hit the area within the next 30 years.

Outline of the Research

The research is an attempt to measure the impact of residency nearby nuclear energy plants, that prone to natural disasters (Earthquakes, tsunamis…) and could cause massive and tragic catastrophes, on the psyche of individuals and local communities. I will examine the effect of such life on the capacity and tendency of the individuals and communities to manage their own lives where a nuclear disaster is an existing threat. Also, I will investigate the rationality behind choosing to reside nearby nuclear plant where many potential threats do exist and how people perceive the risk.

The study aims to discuss human insecurity issues such as health and environmental threats on individuals, and to tackle government intervention and local government efforts to secure the safety of communities living nearby nuclear plants in a uniquely Japanese setting. I hope I will be able to evoke a deeper understanding about the local communities in the target research site, who are experiencing such situation, and to come up with a set of suggestions that can help these communities in the future and be applicable to other communities who reside in similar settings.

Purpose of study and research theme:

The paper aims to consider how local people have perceived, experienced, interpreted and responded to scientific risk of “Nuclear power plants” that is accumulated by expert technocrats that they must balance with their empirical experiences; and how, on the other hand, the framework of nation-states has treated this context of “Nuclear power plants” whose effects can prevail beyond borders. This objective and qualitative research work analysis how individuals shift among fragile, changeable decisions to secure their lives under risky circumstances that are to them now becoming an everyday affair.

This paper revolves around the issues of risk and human security confronting the Japanese people who reside nearby nuclear energy plants today, by targeting some selected communities. I will be focusing on the local communities who live in similar setting to Fukushima (Target research site: Shizuoka_Hamaoka nuclear plant) to see how local people perceived risk particularly before the tragic nuclear disaster in Fukushima nuclear plant following the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, and how the accident affected on their psyche.

The study aims at presenting the forms of human insecurity problems existing in the selected research site, particularly those involving environmental, economic, personal and community security, and to describe how each human security issue interplays with each other and find out how they affect the wellbeing of the people and their attitude towards life and how the government responds to these insecurities. I will share the experiences, voices and life-stories of the people who live with such insecurities (Potential threat from Nuclear plants) and shed light on their behavioral and attitudinal change toward work, self and life after witnessing some minor incidents since the plant was built.

Research Questions:

- How do people residing in close proximity to a major socio-technical hazard/site (Nuclear power plant) live with risk in everyday lives?

- What is it like to live next to a nuclear power plant?

- How far public participation is achieved among citizens?

- How the human security concept is measured and used in the Japanese Nuclear energy context?

Hypotheses

—Threats posed by nuclear plant become ordinary part of people lives, and they get accustomed to them

—Economic benefits overshadow safety concerns among residents

—Residents are very rational in protecting their self-interest

Profile of Main Research Site:

Omaezaki is a city in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. Omaezaki is located at the tip of a peninsula on Japan's Pacific coast. As of 2011, the city had an estimated population of 34,614 and the density of 530 persons per km². The total area was 65.86 km².

Geography

Omaezaki City lies approximately 80 miles (130 km) south of Shizuoka City at the tip of a peninsula of the same name, stretching east into the Pacific Ocean. The majority of the city consists of gentle hills and valleys with some steep cliffs on the peninsula's east coast. Like much of Japan, Shizuoka Prefecture is an earthquake zone, and small tremors frequently occur in the area. Omaezaki is also in an area at risk from tsunami. The rainy season also affects Omaezaki, with typhoons that hit the city between July and September.

Economy

Omaezaki has a long history of commercial fishing and of green tea cultivation and these continue to play a role in the local economy. The Hamaoka Nuclear Power Plant situated in the city has brought investment to it. Another minor source in local economy is Water sports that attract man tourists during the summer, and water sports made possible by strong coastal winds have become as much a part of Omaezaki's identity as that of a rural town.

Hamaoka Nuclear Power Plant

The Hamaoka Nuclear Power Plant (浜岡原子力発電所) is a nuclear power plant located in Omaezaki city, Shizuoka Prefecture, on Japan's east coast, 200 km southwest of Tokyo. It is managed by the Chubu Electric Power Company. There are five units contained at a single site with a net area of 1.6 km2 (395 acres). A sixth unit began construction on December 22, 2008. On January 30, 2009, Hamaoka-1 and Hamaoka-2 were permanently shut down.

On 6 May 2011, Prime Minister Naoto Kan requested the plant be shut down, as an earthquake of magnitude 8.0 or higher is estimated 87% likely to hit the area within the next 30 years. Prime minister Kan wanted to avoid a possible repeat of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. On 9 May 2011, Chubu Electric decided to comply with the government request. In July 2011, a mayor in Shizuoka Prefecture and a group of residents filed a lawsuit seeking the decommissioning of the reactors at the Hamaoka nuclear power plant permanently.

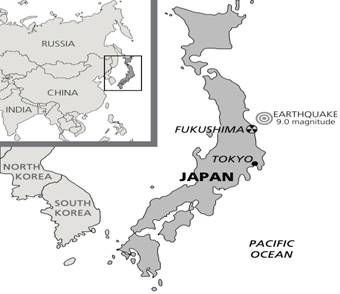

Figure-1 Hamaoka Nuclear Plant in Shizuoka

The Geological Reality of Japan

Japanese people have always faced risk. Their nation is located in one of the most volatile regions of the world, known as the Pacific Ring of Fire. There are 75 active volcanoes in Japan, as well as four intersecting tectonic plates. Japanese people have long lived with the knowledge that an intense earthquake could occur at any time. With more than 300 tiny earthquakes rattling Japan each day, it’s difficult to forecast when a big one will hit.

Figure 2 Geological Reality of Japan

Vulnerability of the Area: Earthquake susceptibility

Hamaoka is built directly over the subduction zone near the junction of two tectonic plates, and a major Tokai earthquake is said to be overdue. The possibility of such a shallow magnitude 8.0 earthquake in the Tokai region was pointed out by Kiyoo Mogi in 1969, 7 months before permission to construct the Hamaoka plant was sought, and by the Coordinating Committee for Earthquake Prediction(CCEP) in 1970, prior to the permission being granted on December 10, 1970. As a consequence, Professor Katsuhiko Ishibashi, a former member of a government panel on nuclear reactor safety, claimed in 2004 that Hamaoka was 'considered to be the most dangerous nuclear power plant in Japan with the potential to create a 原発震災 (domino-effect nuclear power plant earthquake disaster). In 2007, following the 2007 Chūetsu offshore earthquake, Dr Mogi, by then chair of Japan's Coordinating Committee for Earthquake Prediction, called for the immediate closure of the plant.

On 6 May 2011, Japanese prime minister Naoto Kan asked Chubu Electric Power Company, which operates the Hamaoka plant, to halt reactors No.4 and No. 5 and not restart reactor No. 3, which was then offline for regular inspection. Kan said that a science ministry panel on earthquake research has projected an 87% possibility of a magnitude-8-class earthquake hitting the region within 30 years. He said that considering the unique location of the Hamaoka plant, the operator must draw up and implement mid-to-long-term plans to ensure the reactors can withstand the projected Tokai Earthquake and any triggered tsunami. Kan also said that until such plans are implemented, all the reactors should remain out of operation. Chubu Electric has decided to comply with the government request on 9 May 2011.

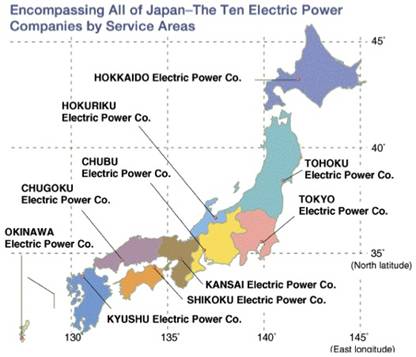

Figure 3:

This is a map of Japan, showing the service area of each power company. In Japan, there are 10 electric power companies, and they are the members of our Federation. All of them are privately owned companies, and they are responsible for local operations from generation to distribution and supplying electricity to their respective service areas.

Nuclear Energy and Host Communities:

During the research, I found out that along with acknowledging Japan’s lack of natural resources, I had to examine the ‘cultures of technology’. Moreover, with a similar focus on culture and social interactions, I had to study local politics in order to understand the rise of the nuclear power industry in post-war Japan. For as Tokyo bureaucrats had realized how much Japan depend on crude oil imports from the Middle East in the 1960s and early 1970s, there would be no industry at all if local communities refused to host power plants. No nuclear power industry, and no high-speed economic growth.

This top-down focus on local communities in the late 1960s and 1970s was one means by which policymakers addressed Japan’s so-called ‘nuclear allergy’.

The new regime of subsidies available to host communities, the Three Power Source Development Laws (1974)[3], also addressed a second problem in post-war Japanese society. Economic growth from the mid-1950s onwards may have been impressively high-speed, but it was unevenly distributed. By the time of the first Oil Shock, much of rural Japan had entered a depopulation crisis. For example, Omaezaki, the small town in Shizuoka prefecture which I have studied, lost a third of its population between 1955 and 1970 alone, as young people in particular sought education and work in distant large cities like Tokyo and Osaka. Attempts to attract new investment by major corporations failed, leaving Omaezaki politicians and bureaucrats ever more desperate in their desire to ‘halt’ depopulation. In the early 1970s, therefore, they struck on the solution of nuclear power, and the first vote to request a power plant (and the central government subsidies that would come with it) was made in 1970. Although Omaezaki’s active pursuit of nuclear power was somewhat unusual, the arguments that made nuclear plants attractive to the majority of townspeople were nevertheless the same as those found in host communities throughout Japan. A Nuclear power station would create jobs—less in the plant itself than in secondary industries, such as construction and services. Nuclear subsidies would bring new infrastructure, such as roads, schools, and care centers for the elderly. Nuclear subsidies would lead to lower municipal taxes and subsidized childcare.

Research Type and Methodology

In line with the objectives and questions, this study is a combination of an exploratory and descriptive research, which later on develops towards explanation. The exploratory part is primarily with regard to the part of the puzzle on the paradigm of human security, and the descriptive part accounts for risk element in the site of Hamaoka nuclear power plant. The explanatory component involves the merging of the two main themes, as an explanation of the problem is attempted.

The main objectives of wanting to understand and explore give reason for the study to be a qualitative research, primarily following an inductive line of reasoning. Utilizing qualitative methods were deemed appropriate for an in-depth understanding toward an explanation of the puzzles. The research was also influenced by Eckstein’s conceptualization[4], which can be categorized as using a combined application of his disciplined-configurative and heuristic types of case studies. Disciplined- configurative case studies are studies where case interpretations are based on established or provisional theories. On the other hand, heuristic studies allow for the refinement of theories applied, as new ones are encountered or new puzzles/questions surface in the process of the research. This research is disciplined-configurative in the sense that the cases encountered were interpreted and analyzed following a thinking based on the human security and risk society framework. It is heuristic in its approach on the analysis, as I encountered new theories and concepts through my study and applied this to the research. The social sciences methods literature also held some compelling reasons for adopting a narrative approach to the in-depth interviews. Firstly, by using a narrative approach, which echoes the conventions of normal conversations, interviews will more at ease, thus reducing incidents of conversational reluctance, and prompting greater disclosure. Secondly, through the active, interpretive process of producing narratives, everyday lived realities can be made intelligible (Czarniawska, 2004). Finally, a narrative approach does not necessarily mean using a single question to elicit a holistic narrative; narrative approach can be combined with more focused questions to avoid the use and production of bland assessments by the narrator to produce more succinct narratives (Flick, 2006).

Also, a rationale for following a narrative approach stems from literatures in relation to risk research. The search came from critiques of the theoretical sociological work under the broad conceptual umbrella of the risk society (Beck, 1992; 1994; 1998; Giddens, 1998; 1999). A common argument here is that theorizing around risk society has become separated from empirical research and is accordingly in danger of overstating the significance of risk in everyday life. In particular, Tulloch and Lupton (2003) suggest that people’s risk discourses need to be examined in the context of their everyday lives: how people experience their lives, their local and other social identities and values all matter to the processes involved in the formation and construction of risk.

3.2.3 Data Gathering

In line with a qualitative research, several data gathering techniques were used. First among these are the three basic modes of qualitative date gathering: in-depth interviews, observation and document analysis. This section briefly describes how these techniques were applied and their significance to the research. Details of the actual research conducted (i.e. fieldwork site and informant profiles, etc.) are discussed later in this chapter. The interviews that were conducted have both “ordinary” community residents and identified key informants as respondents. The interview of residents and village officials were undertaken in their natural settings, within their own communities and in the middle of what their regular activity at a specific time. The fieldwork research sites selected had one required characteristic – that these have been directly affected by living next to a nuclear plant. All respondents were among those who live in the surrounding areas (10 Km radius) of nuclear power plant[5]. This follows another emphasized trait of a qualitative research, the natural setting that maintains the context of the interviews in the respondents’ realities. The key informant interviews served, among others, as a tool to verify the information gathered from the community interviews. Key informants were selected to give different perspectives on the topic from their own experiences in their engagements in Hamaoka nuclear plant community. The interviews were in-depth and lasted no shorter than half an hour. The interviews were mainly conducted in the Japanese language. The observation employed for the research was also of two kinds, participant and non-participant. Non-participant observation particularly took place at the same time as the interviews. Observation of physical surroundings and contextual cues and sub-textual responses served to supplement what was verbally stated. On the other hand, participant observation was accomplished as I have stayed and lived in a small business hotel that was managed by a married couple - one of the respondents, for the duration of the community interviews. This aligned the study towards being a research in human security while enriching the research as a whole[6]. While the period of stay is admittedly not as extensive, it has provided me with valuable snapshots of the “life as lived” in Omaezaki, enriching the study to be not just a study of ordinary life but a study in ordinary life[7]. Also, the fieldwork allowed the researcher to get close to the realities of people who live near the nuclear power plant, and help the researcher to grasp a more precise characterization of their situation.

Document analysis involved the review/analysis of related literature that included both printed and electronic forms of published books, journals, academic studies, media reports and articles, government documents and statistics, historical documents, and presentation materials. I have performed the daunting task of extracting information and insights from reading, reviewing and analyzing the voluminous materials that were acquired in the course of the study, both from the lecture and seminars at Keio University, and from the field research.

These methodologies and techniques allowed for the process of triangulation to validate, verify, corroborate, and/or correct the information gathered to provide for credibility and conformability of the findings, and more confidence in analyzing and discussing conclusions.

Research Time:

Findings in this paper come from continual fieldwork in these following periods. I conducted my fieldwork mainly in the summer vacation of the year 2011 and followed by a sub-fieldwork in the autumn of the same year.

Japan

Tokyo: As the researcher is based in Tokyo, it was convenient to visit as many organizations (NGOs, Anti Nuclear Energy, Energy Sector…) located in the capital as possible during the year of 2011.

Shizuoka Prefecture-Omaezaki Town: 2 Rounds (1 week in August 2011, 5 days in September 2011).

Iwate Prefecture: Rikuzentakata City (2 days volunteering in November).

Research Respondents:

Local individuals reside near the Hamaoka nuclear power plant were primary informants, including those who work in coastal and farming areas:

25 Respondents- Age varied from 22-75- 15 males 10 females Occupation: Farming, Fishing and other businesses (cafés, restaurant, hotels, Students, Surfers …etc).

2 Representatives from local government in Omaezaki city in Shizuoka prefecture.

5 Activists of Anti Nuclear movements in Tokyo.

1 Journalists (Tokyo)

Research Findings

Section 1:Nuclear Power Plant Siting: How it all started

Japan’s Success at Siting Nuclear Power Plants

Given Japan’s experience of the dangers of nuclear weapons, Japan should be less friendly to nuclear power than any other nation, yet it began on a commercial nuclear power program almost as soon as the WW2 ended. Strangely, the only country in the world that ever experienced significant civilian exposure to radioactivity started constructing one of the strongest nuclear programs in the world. Japan has kept going with plans for fast breeder reactors, nuclear fuel recycling, and new plants (Picket 2002). Furthermore, despite early and continuing protests, and Japan’s purported “Nuclear allergy” (核アレルギ), communities continued to volunteer to host plants but the Japanese government use of soft social strategies and incentives is most critical in understanding its current nuclear program.

States, such Japan, often face vexing problems as they try to build mega-projects that serve the needs of citizens as a whole but potentially bring unfavorable consequences into their host communities. Nuclear power plants regularly create adverse reaction in communities. Thus, incentive package are offered to these local communities. Only when policy makers face organized opposition from host communities with strong civil societies and their allies are they prepared to offer a full range of incentives or resort to such social control techniques as persuasion and side payments to win consent. Coercion as a strategy is not favorable; only formulas that include soft social control and incentives are preferable for dealing with future siting dilemmas (Daniel P Aldrich 2007). Nuclear power siting in Japan displays the skills of the country bureaucrats and policy makers in generating these kinds of non-coercive solutions.

With many minor accidents in nuclear plants in Japan, since the beginning of the construction until the Fukushima accident in March 2011, one might imagine that the most vocal opponents would have been found in those host communities. This, however, was not the case. To induce cooperation from host communities, the Japanese government has distributed hundreds of millions of dollars (US) in incentives, loans, infrastructure, and assistance. As a result, the actual and potential host communities have been less concerned with health and environmental hazards and more worried about the loss of revenue streams, taxes, and jobs (Daniel P Aldrich 2007).

Working through official government agencies, such as the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (ANRE, Shigen Enerugi Chō), the Japan Atomic Energy Relations Organization, the Japan Industrial Location Center, and the Center for the Development of Power Supply Regions, the central government has hoped to bring the opinions of these communities in line with national energy plans.

Through institutions such as the Dengen Sanpo (The Three Power Source Development Laws) along with programs targeted at specific demographic groups such as students, fishermen, and local government officials, the Japanese government has created what some have called a “cycle of addiction” in some localities. As all of the communities selected for nuclear power plants are depopulating, coastal communities with weak economic bases, the benefits promised in exchange for hosting reactors have created a “culture of dependency” (NY times, May 30 2011). Once a community accepts a reactor, the money provided creates a new level of spending and expectation about continued purchases, and the only way to maintain that budget is to accept additional plants.

“Nothing other than a nuclear plant will bring money here. That’s for sure. What else can an isolated town like this do except host a nuclear plant?” Despite any anger or health concerns, the population of potential and actual host communities has not become an outspoken critic of Japan’s nuclear policies.

How Omaezaki community ended up hosting a nuclear power plant:

There was a fierce resistance in the Omaezaki 40 year ago when the project was introduced. Angry fishermen vowed to defend areas where they had fished and harvested seaweed for generations. However, when the money started to flow from these operators, people rally in favor and communities appeared willing to nuclear power plant expansion. Even 2 decades later, when the Electric company was considering whether to expand the plant with a third reactor, Omaezaki once again swung into action: this time, to rally in favor. Persuaded by the local fishing cooperative, the town assembly voted 15 to 2 to make a public appeal for construction of the $4 billion reactor. Communities receive a host of subsidies, property and income tax revenues. Paying jobs quickly replaced the community original economic basis, usually farming or fishing. The subsidies encourage not only acceptance of a plant but also, over time, its expansion. That is because subsidies are designed to peak soon after a plant or reactor becomes operational, and then decline.

Largess has made

communities dependent on central government spending and thus unwilling to ask

for robust safety measures- Life income Vs. Safety (Security)

Farmers and fishermen in these communities are regularly offered jobs at government-sponsored facilities to compensate for signing away sea rights in the surrounding fishing area. To further lessen the resistance that fishermen and farmers have shown in the past (because of concerns over “nuclear blight”—potential customers avoiding crops or fish because of fears of nuclear contamination), the government sponsors a yearly fair in Yokohama, in which only communities that host nuclear power plants can display and sell their goods. Finally, the government has created a monumental program called The Three Power Source Development Laws (Dengen Sanpō), which channels roughly $20 million per year to cooperative host communities including the Omaezaki community. The money—which comes not from the politically vulnerable budget, but, instead, from an invisible tax on all electricity use across the nation—purchases roads, buildings, job re-training, medical facilities, and good will. In these rural communities that are, by and large, dying through depopulation and aging, these funds have been providing vital support.

Japan’s choices—to sway public opinion through subsidies, social control tools, and manipulation—have left little room for public debate on the issue of nuclear power. The local residents—whom we see bearing the heaviest burden of the ongoing crisis in Fukushima and who have been exposed to radiation by past accidents at, the fatal accident at Tokaimura, and elsewhere—are seen not as partners, but as targets for policy tools. A plan-rational approach, as Chalmers Johnson might have called it, has placed reactors in areas vulnerable to the threat of tsunami and pushed rural communities into dependence on the economic side payments, which accompany these facilities. Now, as Japan struggles to avert catastrophe, it is the time for a real discussion between civil society and state over the future of nuclear power.

Public Goods vs. Public Bads

While nuclear plants provide electricity to the public, host communities closet to the plants suffer most from the disruptions involved in construction- and any accidents or catastrophes. Even if an accident has not yet occurred, simply living “in the shadow” of a nuclear power plant can lead to psychic costs, and many believe that real estate in such communities loses value as a result.

Authorities place facilities in technically feasible locations where organized resistance from groups within civil society is judged to be the lowest.

In Japan, farmers and fishermen’s cooperatives regularly play an active and vital role in the siting process and often oppose nuclear power plants because of concerns about health risks and contamination of foodstuffs.

Like the one in Omaezaki, communities selected for nuclear power plants are similarly rural, with lower population densities, higher rates of depopulation, and weakening local organizations. Areas that have previously shown themselves susceptible to the siting of public bads display less likelihood of opposing future ones (Daniel P Aldrich 2007). A community that already hosts one nuclear power plant is more likely to be selected for future reactors, just as communities with exposure to a single corrections facility are likely to host future ones (Hoyman 2011). The initial acceptance of a public bad can create a deleterious cycle: the host community that becomes dependent upon the taxes and side payments provided by initial facilities, once it has spent its newly acquired funds, is forced to take on additional facilities to remain financially solvent in what anti-project activists call a “cycle of addiction” (Hasegawa 2004,26). Alternatively, communities that already have one public bad may be habituated to controversial facilities so that additional projects bring with them no new fears- or the may have become dispirited by their initial failure to stop a siting. The communities of Omaezaki on the eastern coast of Japan currently host 5 nuclear reactors.

Along with fears about direct effects on their jobs and health, fishermen and farmers regularly express concern about “nuclear blight”: that is, the contamination of their produce and harvests, and sales lost because of fears or rumors of radioacitivity (See Tabusa 1992, 244).

Areas that would lose or were already losing farmers and fishermen at high rates were judged to have weak civil societies and were targeted as potential host communities.

Wining the hearts and minds in a host community:

To overcome opposition from fishermen’s cooperatives, the utility and the local government used central government funds to fly local residents to visit other communities that were hosting nuclear power plants. (This is an example of the soft social power strategy of habituation: by traveling to host communities and meeting people living in the shadow of nuclear power, the members of potential host communities become more familiar with a technology often perceived as alien and dangerous). The bureaucrats also promised also residents millions of dollars for new roads, medical and old age facilities and loans and subsidies for new businesses. The government distributed to households thousands of pro-nuclear brochures stressing the safety of nuclear power and the country’s need for new reactors. Even school students, in their science classes, used curriculum written by pro-nuclear central government bureaucrats.

Fishermen:

Early on, Japanese government officials recognized the power held by existing networks within local civil society. As nuclear power companies use ocean water for cooling the reactors, the cooperation of fishing cooperatives was vital to the successful planning of the nuclear power industry. Fishermen have various reasons to resist siting: primary among them the potential loss of livelihood. Cooperatives fear that higher water temperature will negatively affect the aquatic ecosystem on which their livelihood depends.

Omaezaki:

Mr. Tamura, 78, recalls how difficult life was as a child in Omaezaki, a tiny fishing village that faces the rough ocean. His father used a tiny wooden skiff to catch squid and bream, which his mother carried on her back to market, walking narrow mountain paths in straw sandals.

In Omaezaki, at first local fishermen adamantly refused to give up rights to the seaweed and fishing grounds near the plant. Fishing corporations eventually accepted compensation payments that have totaled up to $500,000 for each fisherman.

Farmers:

Similar to fishing cooperatives, farmers believed that if their community were to host a nuclear power plant, costumers, fearful of radiation in their products, would cease to buy their goods. Government officials realized that farmers held generalized concerns about health alongside fears about their livelihood. Both government and industry official responded by providing trips to existing host communities to teach them about the normality of life near nuclear plants, allowing them to see how farmers, fishermen, and women coexist peacefully with these facilities (Asahi Shinbun 2011). The center for the development of power supply regions and quasi-governmental corporation set up the popular annual electricity hometown fair (Denki no Furasato Jimanshi) which showcases products from power plant host communities at the Makuhari Messe Convention Center outside Tokyo. In a clever reversal of fears that the presence of a nuclear plant would drive away customers, this fair heightens awareness of local brands from these communities and thus increases their profits. Instead of seeking to hide the source of these vegetables, fruits, fish and other products, the fair celebrates them as contributing to the overall good of Japan. The annual fair brings in as many as 138,000 visitors to see and purchase the goods from more that 270 local groups displaying their wares (Okawara and Baba 1998,9)

Incentives:

As policy instruments, incentives often rely on “tangible payoffs, positive or negative, to induce compliance or encourage utilization” (Schneider and Ingram 1990, 515). Galbraith (1985, 5) would label them forms of “compensatory power” that “wins submission by the offer of affirmative reward”. In Japan’s case, there appear most commonly in the form of compensation and redistributive payments to host to potential host communities. The state provides funds for school, roads, medical facilities, old age homes, and other desirable facilities as a way of altering the locality’s “price” for hosting local public bads. Although citizens may worry about the potential for a nuclear meltdown, the presence of improved infrastructure and new educational opportunities for their children can dampen their enthusiasm for anti-nuclear mobilization. “We know that our town can no longer survive economically without the nuclear plant.”

Japan’s central government continuously provide funds to local communities that host nuclear power plants to help overcome local resistance to siting nuclear power plants. Theses laws redistribute electricity taxes to potential and actual host communities to pay for a variety of programs and facilities; a community can receive up to 20 million per year.

Section 2 Risk Perception

Living with nuclear power in Japan – Hamaoka Nuclear power plant

Background: Previous Nuclear Power Research and Findings

Nuclear power is generally thought of as a uniquely anxiety provoking technology capable of generating intense emotional states such as fear and dread, due to the largely invisible and long-lasting effects it is presumed to have in the event of something going wrong, concerns about radioactive waste, and a historic association with atomic weaponry (see for example, Weart, 1988: Slovic et al., 1991; Joffe, 2003).

In particular, national surveys have shown that dread of nuclear power originate in continued fears regarding potential contamination from radioactive material, health fears (such as developing cancer), and the Chernobyl and Three Mile Island accidents (Slovic, 1987; 1993; Slovic et al, 1991; also see Masco, 2006) and most lately the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident. National surveys also show that, in recent years and particularly after the Fukushima nuclear plant accident, more Japanese people are against nuclear power than support it. It has also been consistently found in survey research, that the acceptability of nuclear power is closely related to levels of institutional trust.

Research that has focused on communities living in very close proximity to nuclear facilities, has found that proximity is associated with somewhat higher levels of support for nuclear power (Eiser et al., 1995). A commonly voiced explanation is that acceptance of, or refusal to overtly criticize, nuclear power by those living close to an existing nuclear facility, caused by the perceived economic benefits it brings to the community, in particular where a community is otherwise economically marginalized (Blowers and Leroy, 1994).

Several psychometric studies have been devoted to determining how high levels of risks are associated with nuclear power. In attempt to determine levels of acceptance related to nuclear risks, (Fischhoff et al. 1978) found that risks associated with nuclear power were judged to be extremely serious and to require immediate action to control. Nuclear power risks were perceived to exceed substantially acceptance levels.

Key to research that has focused on specific nuclear facilities as well as other forms of socio-technical and environmental risk issues present within local communities, is that local context, values and place are all essential components for understanding how people live with (or resist) the notion that they are exposed to risk. From such a perspective ‘place and space’ are constituted by particular socio-cultural, geographical and political characteristics, that are vital to understanding how people construct, perceive and reflect on their experiences of living in close proximity to such hazards (cf. Bickerstaff, 2004; Bickerstaff and Walker, 2001; Masuda and Garvin, 2006; also see Burningham and Thrush, 2004). Eyles et al. (1993) skillfully tie the importance of place to risk and studies of risk perception by stating:

“Risk is now widely recognized to be socially constructed; appraisal and management [of risk] are determined by people’s place in the world and how they see and act in the world. All ideas about the world are in fact rooted in experience and different forms of social organization and their underlying value systems will influence risk perceptions” (pp. 282).

Clearly, social, cultural and political factors represent important aspects of risk perception. Thus, perceptions of risks and associated social constructions of socio-technical and environmental hazards cannot be seen as divorced from the values people develop, as well as processes of identity formation.

The Aim of This Section:

The theoretical, empirical, and policy interests described in the previous section led to the development of a broad research question:

How do people residing in close proximity to a major socio-technical hazard/site (Nuclear power plant) live with risk in everyday lives?

Case Study Area Overview:

Hamaoka Nuclear Power Plant

The Hamaoka Nuclear Power Plant (浜岡原子力発電所) is a nuclear power plant located in Omaezaki city, Shizuoka Prefecture, on Japan's east coast, 200 km southwest of Tokyo. There are five units contained at a single site with a net area of 1.6 km2 (395 acres). A sixth unit began construction on December 22, 2008. On January 30, 2009, Hamaoka-1 and Hamaoka-2 were permanently shut down.

On 6 May 2011, Prime Minister Naoto Kan requested the plant be shut down, as an earthquake of magnitude 8.0 or higher is estimated 87% likely to hit the area within the next 30 years. Kan wanted to avoid a possible repeat of the Fukushima nuclear disaster. On 9 May 2011, Chubu Electric (The operating company) decided to comply with the government request. In July 2011, a mayor in Shizuoka Prefecture and a group of residents filed a lawsuit seeking the decommissioning of the reactors at the Hamaoka nuclear power plant permanently.

Findings:

After intensive analysis of the data and interviews (Questions[8]) collected, the researcher identified some factors associated with living with nuclear risk in everyday life. Although interviews were conducted in the summer of 2011; after the Fukushima Nuclear accident, I relied on a narrative-based approach and tried as much as possible to explore the respondents’ attitudes toward the nuclear power plant before the Fukushima accident and after it.

Main Factors to Be Considered in Risk Perception

Natural vs. Manmade

It makes a great difference in risk perception if the risk or the actual damage is manmade or natural because the latter are more accepted than the former. This involves the control aspect and also incorporates the question of responsibility. Locals are convinced that a manmade damage (Such as the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident in March 2011) could have been avoided by more cautious and careful behavior, or by better knowledge about the risky subject. Locals agree that those responsible have been incompetent and careless, and demand that they take responsibility for their incorrect action. Locals think that it is senseless to certify a negative intention to natural risks such as earthquakes or typhoons. These risks are much more accepted because they can't be improved by more careless behavior. Natural processes are generally better accepted: some believe in God's will, others refer to the laws of nature or simply the world's destiny and fate that must be endured.

“We have no influence whatsoever on a tsunami or a major earthquake.”

Making risk ordinary

In contrast to the assumption that nuclear power is dreadful and feared technology (Weart, 1988), the interviewees often expressed feelings which denied the uniqueness of living close to nuclear power station was present in the majority of the interviewees narrations the process of making the power station, or perhaps more accurately articulating a lack of noteworthiness of the presence of the power station, was revealed in two themes: ----familiarity and habituation (making risk normal).

Familiarity and Habituation

“Before the Fukushima accident, getting used to it is a major aspect of losing fear”

Lay people are much more aware of unknown and new risks. But as they get to know a new risk they gradually habituate and start to accept it. A risk that is present for a long time is attenuated due to habituation, even though the technical risk remains the same (Slovic et al. 1986). This is why known risks are more accepted than unknown risks. Habituation means that one is getting used to a certain risk, whereas familiarity means that the affected person actually knows about the risk. Uncertainty plays a major role in risk perception. The familiarity is higher when a risk is well known to science or the affected person. Nuclear power risks that have nothing to do with the known world are perceived as more dangerous. In this context, a nuclear power plant causes additional problems in the habituation process because locals are unable to perceive these risks with their five senses. Lay people can neither control nor observe such risks by themselves. Another factor influencing familiarity is time.

“It used to be a good sight when we were at sea. We could see that power station and think finally we are nearly home”

Ordinariness is apparent in the interviewees’ familiarity with the nuclear station over the period of their life in the area, as well as the longevity of the presence of the power station. The physicality of the nuclear power plant simply became part of the landscape. For a small number of the interviewees who had moved to Omaezaki as a child or had been born in the area, familiarity was resulted in growing up with the power plant; it was something that had always been there and had been part of their everyday lives. Another source of familiarity was social networks, to which some of the interviewees pointed. For some this came from direct experience of working at the power plant. For others, it was through having a family member, a friend or a neighbor who worked at the power station.

After the Fukushima Accident: Noticing the Extraordinary- Threat and Anxiety as Part of Everyday Life

When respondents were asked about their feeling at the present time, they all have expressed a feeling of anxiety about the safety of the Hamaoka nuclear power plant after witnessing the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident in March 2011.

“Sure, we are all worried in our hearts about whether the same disaster could happen at the Hamaoka nuclear plant”

Both theoretical and empirical analysis suggests that it is when events or symbols of risk and threat intersect with locals’ everyday lives that feeling of threat and anxiety can arise. Minor accidents that are relatively experienced among the locals were narrated as primers of anxiety. However, large explosions or Fukushima-like accident was the most anxiety provoking event so far.

Minor Accidents:

The Japanese public has been opposed to nuclear power since a series of nuclear accidents occurred over the 1990s. The Fukushima nuclear disaster, although the most severe, it has not been the only nuclear accident in Japan. Several nuclear reactor accidents occurred during the 1990s[9]. In 1991, at the Kansai Electric Power Company’s Mihama nuclear power plant in Fukui Prefecture, there was the first ever use of an emergency cooling system causing Japan’s first ever-level 2 nuclear accident. By comparison, on the international nuclear incident scale of 7, Chernobyl was a level 7. In 1995, the government-run experimental breeder reactor at Monju malfunctioned causing a fire and Japan’s most serious sodium leak that had the potential of causing explosions and extensive radiation damage. In 1997, a government-run nuclear-fuel reprocessing plant in Tokaimura suffered a fire and explosion. Radiation leaked into the atmosphere and rated a level 3 on the nuclear incident scale. In 1999, a nuclear research facility in Tokaimura experienced a criticality accident that rated a level 4 on the international scale. Radiation leaked into the atmosphere and has thus far has killed two workers. These accidents have contributed greatly to negative public confidence in government and corporate nuclear oversight.

Attitude toward minor accidents in the past:

Most respondents agreed that a feeling of anxiety was present when they had a minor accident in the nuclear plant, or when heard of accidents occurred in nuclear plants located in other towns in Japan. However, for some, the issue of threat was irrelevant due to distancing through time passing. For others interviewees, they thought the issue of threat and anxiety might remain at the time, but at some point they became reconciled with its existence and simply moved on with their lives.

The Role of the Media

After the Fukushima accident, media has become a tool to amplify the nuclear risk.

“There are daily and continuous reports coming from Fukushima. Whenever we switch on TV or Radio, or even read the newspaper, there are always reports related to the nuclear accident. It is unsettling watching this when you know that you may face similar situation.”

"Minor accidents have been slightly covered by the media, whereas the major accident like the Fukushima one has been fully covered by the media"

Of course modern societies are highly influenced by the media – by television, newspapers, magazines, radio and the Internet. If the media reports a risk, many people suddenly become aware of it and start to worry. Second, if a risk topic appears in the media (news), then the risk must be real because it has made it into the media. In terms of numbers, a media-covered risk might be negligible, like the post-Fukushima accident in March 2011, if compared to other risks that are less extensively covered. In the nuclear case, the inability to control the risk, the unfamiliarity, and other factors certainly played an important role. The topics covered in the media probably reflect the individual psychological perception of risk and additionally serve as a risk perception amplifier. The impact of the media has reached a level of importance that can only be hinted at in this context.

Summary of results of this chapter:

To restate this chapter’s main aim, the researcher’ question was: How do people residing in close proximity to a major socio-technical hazard/site (Nuclear power plant) live with risk in everyday lives?

The discourse across much of interviews data that relate to the power plant in Omaezaki before the Fukushima accident is one which represents the nuclear power station as both ordinary and normal: this includes, viewing them as a familiar part of everyday life and the local place. However, after the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident, the results imply that the respondents view nuclear risks as potentially catastrophic, dread, and uncontrollable. This can be thought of as a process of noticing the extraordinary. Disruption could occur either at moments when media and other sources heightened for people related risks issues (Minor accidents or catastrophe like Fukushima) leading them to reflect upon their local situation, or when more personal events arose such as a case of cancer in a family member or friend. These disruptions brought increasing feeling of anxiety for interviewees, despite the discourse of the power station being familiar and normal in the past.